China’s aggressive policy of planting trees is likely playing a significant role in tempering its climate impacts.

An international team has identified two areas in the country where the scale of carbon dioxide absorption by new forests has been underestimated.

Taken together, these areas account for a little over 35% of China’s entire land carbon “sink”, the group says.

The researchers’ analysis, based on ground and satellite observations, is reported in Nature journal.

A carbon sink is any reservoir – such as peatlands, or forests – that absorbs more carbon than it releases, thereby lowering the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere.

China is the world’s biggest source of human-produced carbon dioxide, responsible for around 28% of global emissions.

But it recently stated an intention to peak those emissions before 2030 and then to move to carbon neutrality by 2060.

The specifics of how the country would reach these goals is not clear, but it inevitably has to include not only deep cuts in fossil fuel use but ways also to pull carbon out of the atmosphere.

“Achieving China’s net-zero target by 2060, recently announced by the Chinese President Xi Jinping, will involve a massive change in energy production and also the growth of sustainable land carbon sinks,” said co-author Prof Yi Liu at the Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP), Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China.

“The afforestation activities described in [our Nature] paper will play a role in achieving that target,” he told BBC News.

China’s increasing leafiness has been evident for some time. Billions of trees have been planted in recent decades, to tackle desertification and soil loss, and to establish vibrant timber and paper industries.

The new study refines estimates for how much CO2 all these extra trees could be taking up as they grow.

The latest analysis examined a host of data sources. These comprised forestry records, satellite remote-sensing measurements of vegetation greenness, soil water availability; and observations of CO2, again made from space but also from direct sampling of the air at ground level.

“China is one of the major global emitters of CO2 but how much is absorbed by its forests is very uncertain,” said the IAP scientist Jing Wang, the report’s lead author.

“Working with CO2 data collected by the Chinese Meteorological Administration we have been able to locate and quantify how much CO2 is absorbed by Chinese forests.”

The two previously under-appreciated carbon sink areas are centred on China’s southwest, in Yunnan, Guizhou and Guangxi provinces; and its northeast, particularly Heilongjiang and Jilin provinces.

The land biosphere over southwest China, by far the largest single region of uptake, represents a sink of about -0.35 petagrams per year, representing 31.5% of the Chinese land carbon sink.

A petagram is a billion tonnes.

The land biosphere over northeast China, the researchers say, is seasonal, so it takes up carbon during the growing season but emits carbon otherwise. Its net annual balance is roughly -0.05 petagrams per year, representing about 4.5% of the Chinese land carbon sink.

To put these numbers in context, the group adds, China was emitting 2.67 petagrams of carbon as a consequence of fossil fuel use in 2017.

Prof Paul Palmer, a co-author from Edinburgh University, UK, said the size of the forest sinks might surprise people but pointed to the very good agreement between space and in situ measurements as reason to have confidence in the analysis.

“Bold scientific statements must be supported by massive amounts of evidence and this is what we have done in this study,” the NERC National Centre of Earth Observation scientist told BBC News.

“We have collected together a range of ground-based and satellite data-driven evidence to form a consistent and robust narrative about the Chinese carbon cycle.”

Prof Shaun Quegan from Sheffield University, UK, studies Earth’s carbon balance but was not involved in this research.

He said the extent of the northeast sink was not a surprise to him, but the southwest one was. But he cautioned that new forests’ ability to draw down carbon declines with time as the growth rate declines and the systems move towards a more steady state.

“This paper clearly illustrates how multiple sources of evidence from space data can increase our confidence in carbon flux estimates based on sparse ground data,” he said.

“This augurs well for the use of the new generation of space sensors to aid nations’ efforts to meet their commitments under the Paris Agreement.”

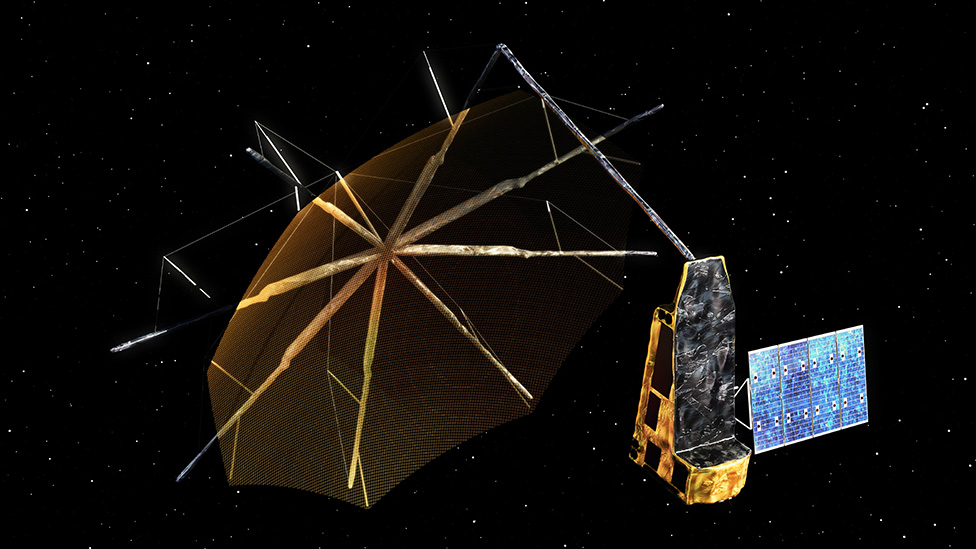

Prof Quegan is the lead scientist on Europe’s upcoming Biomass mission, a radar spacecraft that will essentially weigh forests from orbit. It will be able to tell where exactly the carbon is being stored, be it in tree trunks, in the soil or somewhere else.

Another future satellite project of note in this context is the planned EU Sentinel mission (currently codenamed CO2M) to measure CO2 in the atmosphere at very high resolution.

Richard Black is director of the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU), a non-profit think-tank working on climate change and energy issues.

He commented: “With China setting out its ambition for net zero, it’s obviously crucial to know the size of the national carbon sink, so this is an important study.

“However, although the forest sink is bigger than thought, no-one should mistake this as constituting a ‘free pass’ way to reach net zero. For one thing, carbon absorption will be needed to compensate for ongoing emissions of all greenhouse gases, not just CO2; for another, the carbon balance of China’s forests may be compromised by climate change impacts, as we’re seeing now in places such as California, Australia and Russia.”